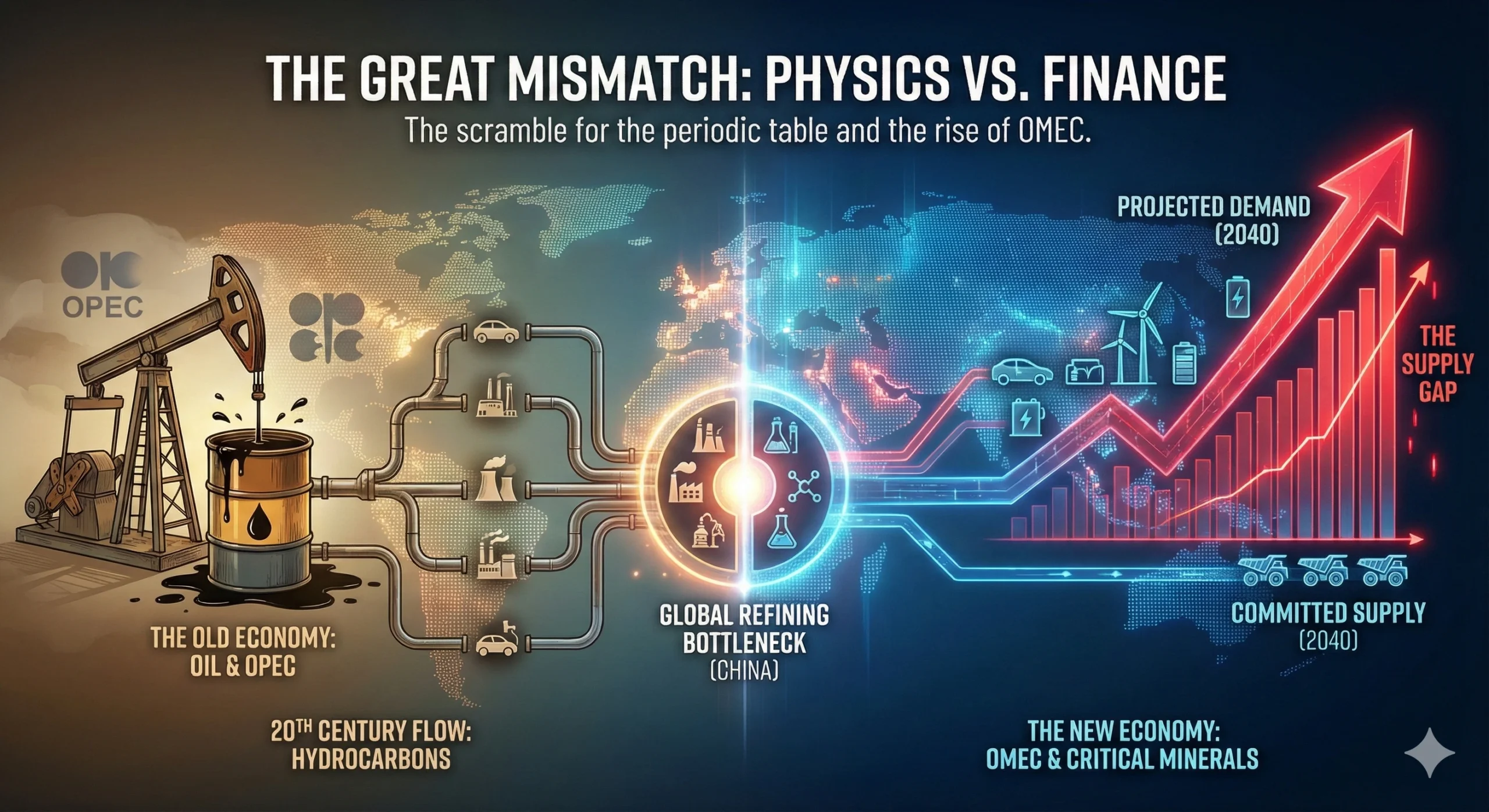

The “Green Energy Transition” is often discussed as an environmental or moral imperative. In financial and geopolitical terms, however, it is a massive industrial re-tooling that relies on a specific set of raw materials: Lithium, Copper, Cobalt, Nickel, and Rare Earth Elements. Demand for these materials is exploding, but supply is struggling to leave the ground.

This is the scramble for the Periodic Table. It will define the winners and losers of the next economic cycle, creating new alliances that look less like OPEC (Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries) and more like an “OMEC”—an Organization of Mineral Exporting Countries. For investors, understanding this supply chain is no longer optional—it is the baseline for navigating the future economy.

The Great Mismatch: Physics vs. Finance

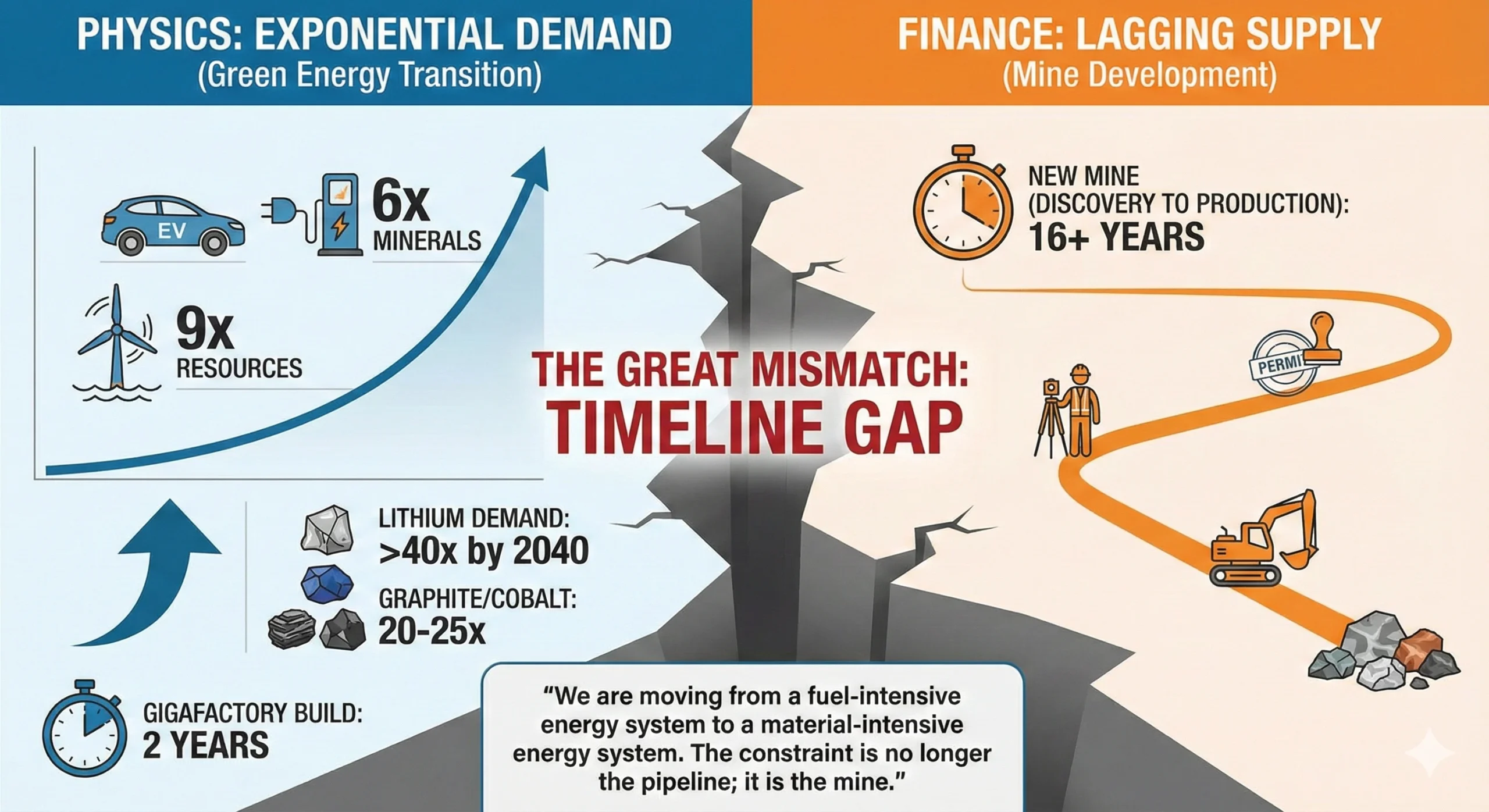

To understand the scale of the problem, one must look at the physical requirements of modern technology. An electric vehicle (EV) requires six times the mineral inputs of a conventional car. An offshore wind farm requires nine times more mineral resources than a gas-fired power plant.

The International Energy Agency (IEA) projects that to meet global climate goals by 2040, the demand for lithium needs to grow by over 40 times. Graphite and cobalt demand needs to grow by 20-25 times.

Here is the economic problem: You can build a Gigafactory for batteries in two years. It takes, on average, 16 years to bring a new mine from discovery to production. We have a timeline mismatch. We are building the factories to consume the minerals before we have dug the holes to find them.

“We are moving from a fuel-intensive energy system to a material-intensive energy system. The constraint is no longer the pipeline; it is the mine.”

The New Geopolitical Chokepoint

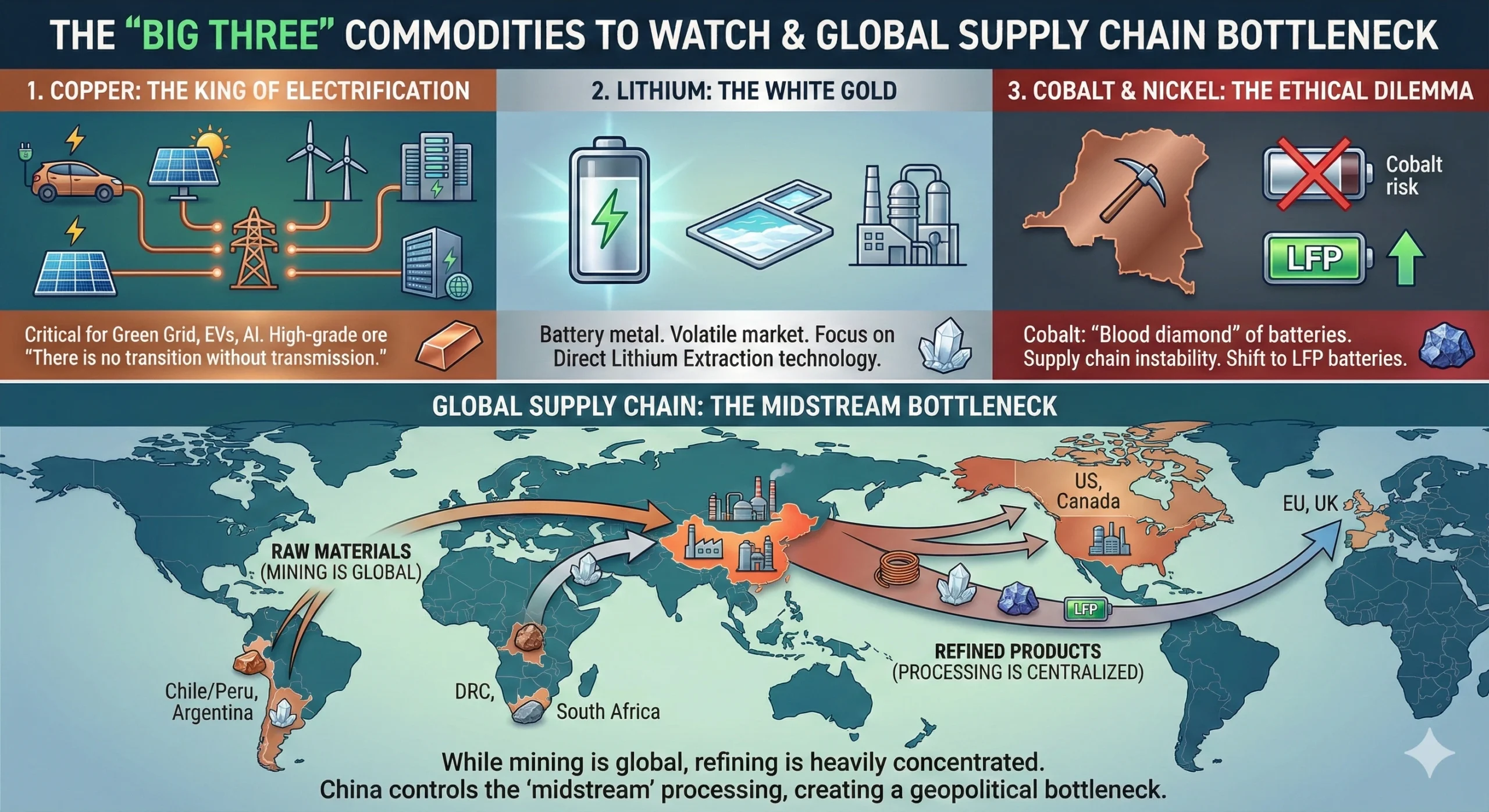

In the oil era, the world worried about the Strait of Hormuz. In the mineral era, the chokepoint is processing capacity.

While minerals are found all over the world (Lithium in Chile/Australia, Cobalt in Congo, Nickel in Indonesia), the processing of these minerals is heavily concentrated. Currently, China processes nearly 60% of the world’s lithium, 65% of cobalt, and nearly 90% of rare earth elements.

This creates a singular point of failure for Western supply chains. The US and Europe are frantically attempting to “friend-shore” these supply chains—signing deals with Australia, Canada, and various African nations to bypass Chinese refineries. This bifurcation of the global market is creating a “dual-price” world: one price for “clean, secure” minerals compliant with Western subsidies (like the US Inflation Reduction Act), and another price for everything else.

The “Big Three” Commodities to Watch

Investors often treat commodities as a monolith, but each metal has its own distinct economic personality.

1. Copper: The King of Electrification

Copper is the most critical metal of all. You cannot have a green grid without it. Solar, wind, EVs, and even AI data centers are massive copper consumers. Unlike lithium, which is abundant, high-grade copper is becoming harder to find. Old mines in Chile and Peru are seeing their ore grades decline. As the saying goes in the industry: “There is no transition without transmission.”

2. Lithium: The White Gold

Lithium is the battery metal. The market is currently volatile, swinging from shortage to surplus as new supply comes online. However, the long-term trend is up. The key for investors here is not just mining, but the processing technology—companies that can extract lithium from brine more efficiently (Direct Lithium Extraction) are the new tech darlings.

3. Cobalt & Nickel: The Ethical Dilemma

Cobalt is the “blood diamond” of the battery world, with a significant portion mined in unstable conditions in the DRC. This has led battery makers to actively try to engineer cobalt out of the battery (shifting to LFP batteries). This technological risk makes cobalt a dangerous long-term hold compared to Copper.

The Investment Thesis: Pick and Shovels

How does a portfolio capture this theme? Buying a mining stock is the obvious answer, but it carries operational risk (strikes, floods, nationalization).

A smarter approach often involves the “Pick and Shovel” plays:

- The Recyclers: As the first generation of EVs retires, “Urban Mining” (recycling batteries) will become a major source of supply. Companies that can reclaim lithium and cobalt from dead batteries effectively become domestic mines.

- The Royalty Companies: These firms provide upfront capital to miners in exchange for a percentage of future revenue. They get the upside of high commodity prices without the risk of running the tractor or dealing with labor unions.

- The Equipment Makers: The massive capital expenditure (Capex) required to build these mines means billions of dollars flowing to the companies that make the excavators, the crushers, and the autonomous haul trucks.

Also read: Why Africa holds key to worlds green energy transition

Risks: The Resource Curse

The path forward is not a straight line. Resource nationalism is rising. Countries like Mexico, Chile, and Indonesia are increasingly demanding a larger share of the profits, or threatening to nationalize assets entirely. An investor might own a great mine on paper, but if the local government changes the tax law overnight, the profit margin evaporates.

Furthermore, technology moves fast. If the world shifts to Solid State Batteries or Sodium-Ion batteries, the demand for specific metals could drop overnight. Diversification across the mineral spectrum is the only hedge against technological obsolescence.

The Bottom Line

The scramble for resources is not a temporary trend; it is the industrial logic of the next two decades. We are rebuilding the global energy infrastructure from scratch. That requires a mountain of metal.

For the last 100 years, if you wanted to hedge inflation or play geopolitics, you bought Gold or Oil. In 2026, you buy Copper and Lithium. The Periodic Table is effectively being repriced, and portfolios that don’t account for this material reality risk being left behind in the old economy.